Blog article

Break Out Of Your Comfort Zone And Become An Everyday Hero

Posted by Adela SchickerWhy are some people bad and some heroes? What goes through the mind of evil people? And why, on the contrary, do some people stand out of the crowd and perform heroic acts? Given what we know about heroism, how would we behave if we were in the shoes of an American prison guard in Iraq?

This video is part of an online minicourse. If you want to discover more interesting concepts, check it out.

Professor Philip Zimbardo, one of the most respected psychologists in the world, has dedicated his life to these questions. Not long ago, a few colleagues and I had the opportunity to meet him personally and discuss this topic.

Bad Sheep and the Blind Crowd

Zimbardo’s famous Stanford Prison Experiment and research found real-world corroboration with the Abu Ghraib prison guards showing that even moderate, and originally decent people, can do very bad deeds under certain influences and circumstances. It doesn’t matter if the person is a “family man”, if he’s religious, or even if he has an impeccable reputation.

Zimbardo took a group of student volunteers for his prison experiment and staged prison cells in a basement. Half of the volunteers became prison guards and the other half became prisoners. After just a few days, the guards enacted very cruel behaviors – humiliation, abuse, and evil thought-out punishments. The abuse was so bad the experiment had to be terminated.

Abu Ghraib was a real prison in Iraq with American Guards and Iraqi prisoners. Equally cruel behaviors were revealed between the guards and prisoners. Yet, since this was not a controlled experiment, this situation was not terminated after a few days. The evil in Abu Ghraib grew for a long time...

What happened to make these people act so cruelly? Zimbardo’s experiment shows the big influence of the so-called bystander effect. It’s the phenomenon that occurs when a person does something because others are doing it too. It occurs because the person doesn’t want to be subjected to social pressure that would distinguish him or her from the crowd.

“The world will not be destroyed by those who do evil, but by those who are watching them without doing anything.”

-- Albert Einstein, theoretical physicist

It’s uncomfortable for many people to leave the crowd, so they go along with it, even if they’d rather go elsewhere. The bystander effect may actually contribute to homelessness. Some homeless are more comfortable staying homeless than looking for a job and being seen as a traitor by their colleagues.

Sometimes it only takes someone in higher authority doing something for a crowd to follow. Just look at recent history, like for example Germany in the 1930s. Psychopaths don’t perform the brutal acts of war, rather it’s generally normal people who are exposed to the pressures of the surrounding circumstances doing it.

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.”

-- Edmund Burke, Irish political philosopher

The Hero Is a Deviant Person

What does it take for a person to stand out of the crowd and point out flawed behavior? Why are some people able to stop by an accident while others walk right by? Zimbardo labeled these people heroes. He says that heroic skills can be learned gradually. His research shows that a hero isn’t born, but cultivated.

Zimbardo took a black pen to our meeting and drew a black dot on his forehead. He wanted to show us a simple way to practice heroism. If a person has this black dot on his or her forehead all day and rides the bus, he or she gets used to other’s strange stares. It gets the person into the habit of being different, of standing out from the crowd. The person gets used to leaving the social comfort zone and the //unpleasant social pressure stops affecting the individual.**

Training Heroism

Training heroism makes it easier to step out of the crowd. Many people pass a car accident simply because no one else has stopped. Zimbardo says heroism doesn’t let the environment influence a person; he or she would stop and provide assistance regardless of what others do. It’s the ability to stand out of the crowd and perform an action first. Heroes manage to be different because they’re already used to it. According to Zimbardo, a hero is a bit of a deviant person.

“The core of your life can be reduced to two types of actions: those taken and those not taken.”

-- Philip Zimbardo, psychology professor

One of Zimbardo’s colleagues was a hero in one situation during the Stanford Prison Experiment. She stepped out of the crowd during the time of the experiment and forced him to stop it (Zimbardo later married her). In Abu Ghraib, a young soldier was the hero when he was able to leave his comfort zone and bring attention to the situation at the prison.

Become A Hero With Our Free 20-Minute Mini Course

The Heroism of Everyday Life – Leaving The Comfort Zone

The word heroism usually refers to extraordinary actions, but it should also be remembered as a skill we use every day. Jumping down in the subway tracks to save a life and avoiding delaying important daily tasks have the same principles. The difference is the level of conscious skill used to leave the comfort zone.

In order to take action, it’s often necessary to get out of the comfort zone. If we’re supposed to get up in the morning, we turn off the alarm and leave our warm bed. If we want to help at an accident, we have to stop, get out of our car, and take action. Both cases deal with intentionally getting out of the comfort zone, though the magnitude of the effort may be different.

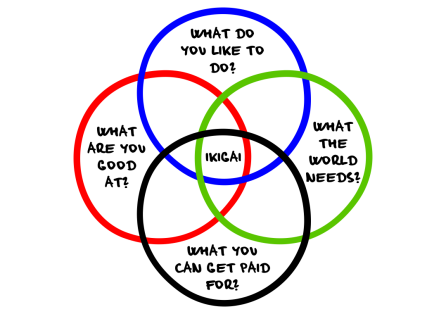

Learning to leave the comfort zone is an essential skill. Most of the important actions taken in our lives are those outside of our comfort zone. It can be a physical or social action. If we want to meet people, we first have to reach out. To succeed in business, we must be able to arrange business meetings or meet people at networking events. In order to follow your life’s vision, it’s sometimes necessary to go a different direction than the rest of the crowd.

“The one who follows the crowd will usually go no further than the crowd. Those who walk alone are likely to find themselves in places no one has ever been before.”

-- Albert Einstein, theoretical physicist

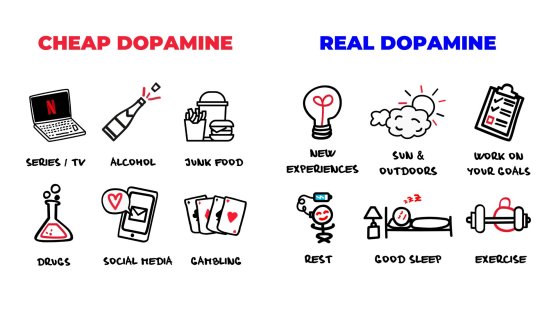

Leaving the comfort zone is really important for achieving satisfaction. As we successfully leave and expand our comfort zones, our brain then rewards us with dopamine, which is an organic chemical responsible for our satisfaction.

How Can You Train Heroism?

Since heroism is considered a micro habit, it is good to constantly think about it. It’s also good to get out of the comfort zone and take action. Whenever you can, try to leave your comfort zone. Talk to the person sitting next to you on the bus. When you don’t feel like doing anything, try taking an action that is the hardest for you to do.

Daily heroism can be trained by using a method when you first wake up. It lies in doing the most unpleasant task first thing in the morning. This morning heroism will encourage you to take other heroic actions throughout the day.

If you are thinking of performing a heroic action, it’s good to follow the samurai rule of three seconds. Take action within five heartbeats. If you start to overthink the action, your mind will have the tendency to create justifications on why you should stay within your comfort zone.

Evil as a biased notion of good

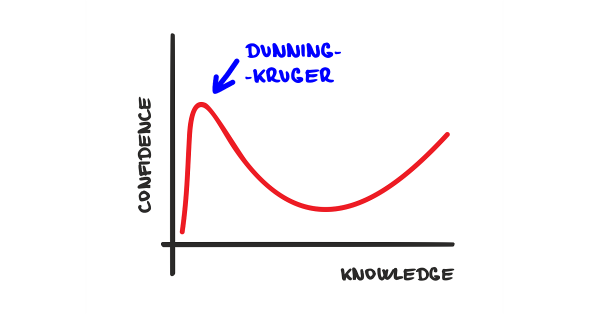

Due to the Dunning-Kruger Effect, many people think that they’re doing something good, even when they’re really doing something bad. Hitler and Stalin wanted to fulfill their vision of social welfare. Similarly, for example, interviews with mass murderers show that many of them don’t even realize that what they’re doing is wrong.

“Most human suffering caused by man is due to his belief in things that are proven to be false.”

-- Bertrand Russell, logic and philosopher, Nobel Prize winner

So how can you stop this unconscious evil? Anyone’s intentional actions that have a significant social impact should first look at the objective consequences. People should admit that their idea of good may be incorrect and can, in fact, be bad in the end. It’s no wonder they say that the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

What exactly is good vs. evil?

This philosophical question has been troubled people throughout history. Finding the correct answer in this field is problematic, and that’s why I’ll state my own subjective opinion.

I generally define evil as an individual’s actions that harm other people or groups that the individual is part of. Similar to the behavior of cancer cells, which harm the body that they’re part of.

I would define “good” as an individual’s actions that lead to an improved function of the whole group that the individual is part of. It’s the ability to perform unselfish cooperative acts that leads to the development and growth of other people and the group as a whole. This definition puts a lot of activities in the gray zone, where it’s hard to determine the final impact. Overall, finding some sort of objective good is a never-ending journey. Let’s be a hero every day by also questioning our own views. Trying to find out which views we hold are false is one of the biggest actions we can take to get out of our comfort zone.

“Follow the man who seeks the truth; run from the man who has found it.”

-- Vaclav Havel, president od Czech Republic

VIDEO: The Psychology of Evil

Additional sources

- Book: Haney, C.; Banks, W. C.; Zimbardo, P. G.: Study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison. Naval Research Reviews, 9, 1–17. Washington, DC: Office of Naval Research. 1973.

- Book: Zimbardo, P.: The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil. Rider & Co; 1st edition edition. 576 pg. ISBN: 978-1844135776.